CIMMYT is transforming agrifood systems to become climate-smart, resilient and inclusive. For example, fostering collaboration between machine manufacturers and farmers in India and in Benin to co-design the equipment that smallholders need to make farming an attractive career. This international partnership is a systemic change, to meet smallholder farmers’ needs for innovation in the future. Pakistani farmers are now planting heat-adapted wheat varieties on a massive scale, transforming the country’s agrifood system towards self-sufficiency in cereals. In India and Mexico, wheat and maize farmers are transforming their agrifood systems with conservation agriculture, to improve soil fertility, save water, and produce more food while adapting to climate change. Breeding and delivering the latest maize hybrids require new national seed systems, as CIMMYT and partners are building in Bhutan. Systems thinking is necessary to link producers with seed supplies, machinery, and markets, as is being explored with a farmers’ hub in Nigeria.

In 2021, an early warning system helped to prevent a rust disease outbreak on wheat in Ethiopia, allowing farmers to reap a record-breaking harvest. In 2023, CIMMYT and partners expanded crop disease surveillance systems to protect wheat in food-vulnerable areas of East Africa and South Asia, and to monitor maize lethal necrosis (MLN) in East and Southern Africa.

CIMMYT partnered with Cornell University to launch the Wheat Disease Early Warning Advisory System (Wheat DEWAS), funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). Relying on expertise from 23 research and academic organizations from sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, Europe, the United States, and Mexico, Wheat DEWAS rapidly forecasts outbreaks of rust and blast diseases.

Through Wheat DEWAS, CIMMYT is actively engaged with partners to promote strategic alignment around common goals.

CIMMYT partners with national governments and global institutions to scale up innovative forecasting of crop disease, using big data and new ICT infrastructure to transform agrifood systems. For example, the Global Rust Reference Center, Aarhus University, Penn State University, Cornell, the University of Minnesota, Cambridge University, and Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University are helping to manage large data sets. They are reducing gaps in knowledge management to support evidence-based decision making. Discoveries made by Wheat DEWAS will also benefit future surveillance systems for other pathogens, in other crops. Another big data tool by CIMMYT gives policymakers insights into cost-effective ways to make agriculture part of the solution to climate change.

A quarter of the greenhouse gas emitted by humans comes from agriculture, livestock and forestry. As a global thought leader in climate resilience, CIMMYT realized that there was an opportunity to design agricultural policy that would help meet the Paris Agreement’s 2030 climate goals. Policy makers needed a practical tool to identify promising strategies for climate-friendly farming.

CIMMYT created a rapid assessment tool to find cost-effective ways to reduce agricultural emissions. As a large country with a crucial farming sector, Mexico was ideally suited to test this global innovation. CIMMYT found that Mexico’s total emissions from crop and livestock production were about 147.45 million tons of carbon. However, these emissions were slightly offset by sequestrations from forestry and other land use (FOLU) of about 148.35 million tons. This left a small net sequestration of about 0.90 million tons of carbon. CIMMYT’s assessment tool determined that Mexico could cut a further 88 million tons of carbon emissions annually. This would make agriculture, livestock and forestry an important sink of greenhouse gases. The transition could be made fairly painlessly, by phasing out fertilizer subsidies, which reward the inefficient use of nitrogen, and contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Adopting proven CIMMYT practices like minimum tillage and precision leveling of fields will also lower emissions by optimizing fuel, fertilizer, and irrigation water. Methane emissions from livestock can be managed with composting and biodigesters. “Adopting these practices will not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but they will also help increase productivity,” said CIMMYT’s retired Principal Scientist, Iván Ortiz-Monasterio.

Results from India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Thailand show that CIMMYT’s framework is applicable far beyond Mexico. The framework uses big data for agricultural research and development, reflecting CIMMYT’s capacity to implement an ICT infrastructure, handle data and support evidence-based decision making. The tool will help decision makers recognize that agrifood systems are interlinked agroecosystems that sustain and enhance biodiversity, soil health and environmental quality. Any country can use the tool to find cost-effective ways to mitigate climate change. Sharing this tool with the global community will help to meet the Paris Agreement’s 2030 climate goals by giving decision makers a method to craft national policy that lowers greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, livestock and forestry. CIMMYT’s big data models are informed by a deep experience, transforming agrifood systems across the world, from Mexico, to Malawi, and India.

Since 2010, at least 33,348 farmers have participated in demonstration events organized by CIMMYT’s MasAgro initiative. By training 5,935 technicians and extension agents, MasAgro helped some 500,000 farmers to adopt improved maize and wheat varieties and soil and water conservation techniques on over one million hectares in 30 states of Mexico. These farmers are producing more food and improving their livelihoods, as they have boosted maize yields by 20%, with a 23% increase in income. Wheat farmers improved their yields by 3% and their incomes by 4%. In 2023 the question was how to sustain this momentum?

In 2023 the governor of the state of Guanajuato visited CIMMYT to review progress and agree on future activities with MasAgro, which is supported by CIMMYT in partnership with Mexico’s Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development (SADER), and Mexican state governments. Service centers rent and repair machinery, so farmers can adopt conservation agriculture practices, such as zero tillage and using crop residues as mulch. Impressive achievements in data management, such as mapping the soil on over 100,000 hectares, have helped Guanajuato farmers to cut costs, use fertilizer more efficiently, and to stop burning crop residues. This improves soil and water management, helping farmers to adapt to climate change. MasAgro has been cited as a model by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and at the G20 summit of 2018. MasAgro demonstrates how CIMMYT’s vision on agrifood systems is underpinning strategic dialog and informing policy. CIMMYT’s Director General, Bram Govaerts, received the 2014 Norman Borlaug Field Award for leading MasAgro’s farmer outreach component. As Govaerts explains, “CIMMYT’s integrated development approach overcomes government transitions, annual budget constraints, and win-or-lose rivalries between stakeholders, in favor of equity, profitability, and resilience.”

MasAgro gathered over 2 billion data points of maize and wheat genetics, the largest sample ever taken. The world’s scientists can now access this data online. This ICT infrastructure typifies CIMMYT’s global leadership in digital transformation and capacity to exploit big data for research for development (R4D). Building on MasAgro, CIMMYT is a major partner in the CGIAR initiative, AgriLAC Resiliente, which will benefit vulnerable communities by improving food security, and mitigating climate hazards in Colombia, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru. In this way, MasAgro’s model will contribute to curbing migration from Central America by offering local farmers proven pathways to develop more productive, resilient and inclusive farming systems. MasAgro’s insights are also being adapted to tropical rainfed conditions in eastern and southern Africa, encouraging smallholder farmers to co-develop and adopt proven, and locally-tested innovations. CIMMYT’s experience with vulnerable communities is also highlighted by decades of participatory research in Malawi.

Global mandates, like the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), often operate at a scale too broad to be easily grasped by local stakeholders. CIMMYT researchers asked if participatory action research (PAR), a method for systematically engaging scientists with stakeholders, could bridge the SDGs with local needs.

A 2023 article published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment describes 20 years of PAR in Malawi by CIMMYT and partners, including the US Department of Agriculture, Michigan State University, Cornell University, the University of Zimbabwe,

Taylor University, Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, as well as Soil, Food and Healthy Communities (Malawi). “PAR gives a voice to farmers, speeding up impact,” said Sieglinde Snapp, lead author and director of the Sustainable Agrifood Systems program at CIMMYT. “This study showed that scientific contributions are possible through PAR, which generates knowledge step-by-step. Stakeholders co-create flexible solutions with researchers.” For example, PAR in Malawi showed that farmers preferred agro-forestry plots that included shrubby food crops, which also enhance soil fertility. The research involved hundreds of communities, on many topics. For example, Malawi has spent millions of dollars subsidizing fertilizer for hybrid maize.

One farmer, B. Maleko, exemplifies the collaboration with CIMMYT scientists. At her experimental plot in Mwansambo in Malawi, she explained how in 2006, only five households in her community had adopted conservation agriculture, on a mere 1.5 hectares. But by 2012, work by experimenting farmers had shown that conservation

agriculture and intercropping with groundnuts and other legumes could save on production costs, while producing more food. In the end, 947 households adopted this sustainable, scalable solution on 786.4 hectares, contributing to SDG goal 1 (No Poverty) and goal 2 (Zero Hunger).

Two decades of experience with PAR show how the aspirations of smallholder farmers can drive the agrifood research agenda. Farmer-researcher partnerships have honed innovations like conservation agriculture and intercropping with legumes, enabling farmers to produce enough food to feed their families, while staying within planetary boundaries. PAR has demonstrated the value of transdisciplinary and participatory research in various other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Asia. PAR takes research to scale, highlighting CIMMYT’s global leadership in systems transformation to be more inclusive and resilient. Malawi is just one of many examples

of CIMMYT’s collegial relationship with innovative farmers, including smallholders in India who are transforming their agrifood system with climate-smart farming practices.

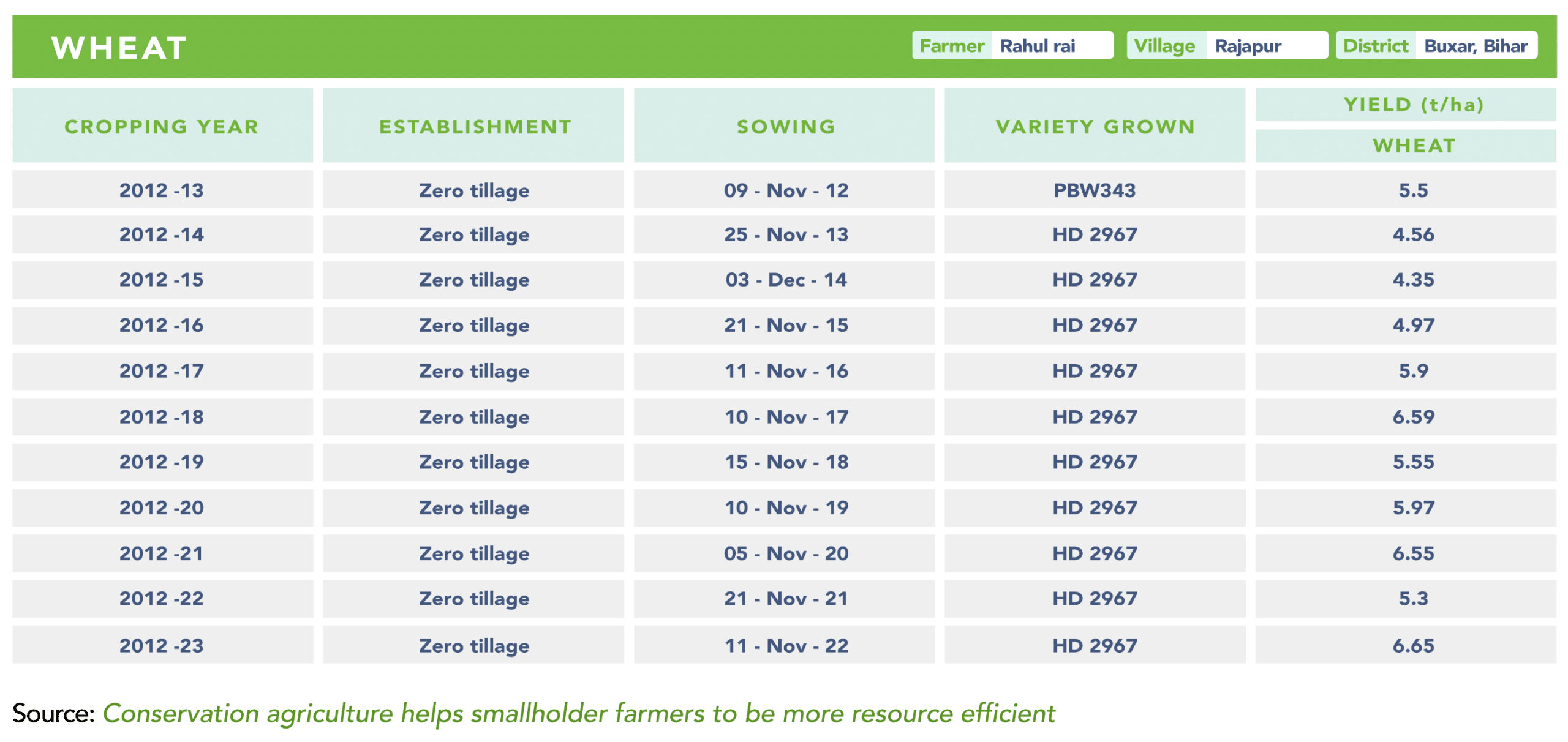

In Bihar, India, wheat yields are threatened by rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, soil erosion, and depleted water tables. In India, 14% of greenhouse gas emissions are linked to agriculture.

CIMMYT promotes conservation agriculture in South Asia with zero tillage to manage soil erosion, crop rotation to improve soil fertility, and mulching with crop residues to hold in soil moisture. Conservation agriculture also reduces farmers’ costs. Planting wheat early increases yields by allowing plants to mature during cooler weather. In India, Bangladesh and Nepal, CIMMYT is leading a strategic partnership with other

CGIAR centers: the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), with funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. CIMMYT and CGIAR have been promoting conservation agriculture in Bihar since 2010, in partnership with farmer centers (KVKs), and government extension agents from the local agriculture departments. In Rajapur village, 100% of the farmers have adopted zero tillage in wheat. Farmer Rahul Rai first met CIMMYT and KVK scientists in 2011,

who were promoting conservation agriculture in a village near his home. Overcome by curiosity, he immediately planted a few acres of his family’s farm to early, zero-tillage wheat. He also adopted early sowing, doubling his wheat yield. Data from his farm shows steady improvement in yields. Until 2014, his wheat yield was about 3.5 to 4 tons/hectare, rising to around 5.5 tons/hectare in 2023 (see figure below). These innovations helped Rahul Rai and other farmers to save on input costs while avoiding some of the labor-intensive practices of conventional tillage. CIMMYT and partners are now sharing these innovations widely through exposure visits, demonstration trials on farmers’ fields, and support for machines and quality seeds, in collaboration with private service providers. Rahul Rai hosts one of these demonstration plots on his own farm. He proudly explains, “The data from my fields on the benefits of conservation agriculture help to promote best practices across our state.”

CIMMYT is now collaborating with more farmers and policymakers to expand conservation agriculture across South Asia. One farm, and one village at a time, conservation agriculture is steadily expanding across the region, producing more food, and conserving soil, while lowering greenhouse gas emissions. Conservation agriculture in Bihar will improve soil health and water use for generations, reducing dependency on inputs and mitigating climate risks. This is a clear example of progress towards CIMMYT’s 2030 vision of resilient agrifood systems, involving farmers in a participatory research agenda. Elsewhere, CIMMYT and partners are scaling up participatory research, as plant breeders include women and men across Africa in trials to find the best maize for the continent’s future.

Women farmers in Africa are some of the hardest hit by climate change. However, new climate-resilient maize varieties can help farm communities achieve food security, sustainably. CIMMYT plant breeders are already creating crop varieties that include the

traits demanded by women. However, CIMMYT also realizes that gendered differences in farming practices still lead to lower yields for many female farmers.

Asking women what they want in a new crop variety is necessary, but it’s not enough. Women farmers must also be involved in testing the new maize before breeders release it. CIMMYT has regional maize breeding networks across eastern and southern

Africa, in partnership with the National Agricultural Research and Extension Systems (NARES). CIMMYT’s leadership in these networks ensures that smallholders will have nutritious maize varieties, bred to be climate-resilient, and responsive to women’s demands. To test new maize hybrids under real farm conditions, the CIMMYT-NARES network held trials on 400 farms in southern Africa, and more in eastern Africa. Over 40% of these experiments were managed by women farmers, who evaluated the new maize using their own practices, giving valuable feedback to the breeders. Another 30% of the trials were jointly managed by women and men, which CIMMYT research has shown is common in the region. In 2023, a remarkable 208,343 metric tons of certified seed of CGIAR-related, stress-tolerant maize varieties were produced. Planted by about 9.2 million households on 8.5 million hectares, across 13 African countries, this maize helped to feed some 56 million people. A widely-accepted maize variety scales up innovation to millions of people.

CIMMYT-NARES networks are transforming gender-inclusive research, collaborating with empowered women farmers to conduct trials of new maize. CIMMYT’s global leadership ensures that improved maize meets the needs of all farmers, and makes sustainable farming more rewarding for men and women farmers. CIMMYT’s strategic partnerships within CGIAR, and with NARES across Africa are proving to be an effective environment for co-creating and scaling relevant, accessible technologies. While plant breeding is crucial, to be effective it must often be backstopped by creating new seed systems, like the one now transforming agrifood systems in Bhutan.

In Bhutan, maize was the second food crop, after rice. Yet farmers often failed to find the seed of varieties they wanted. Maize yields fell between 2016 and 2021. At the same time, rural-urban migration, the growth of cities, and climate change removed two-thirds (64%) of the land devoted to maize, and half (55%) of the rice area. Bhutan was then forced to import grains. To foster self-sufficiency, and food security, in 2020, Bhutan released its first climate-resilient maize hybrid, Wengkhar Hybrid Maize-1 (WHM-1), which was sourced from CIMMYT. However, Bhutan needed to strengthen its seed system’s capacity to produce hybrid maize seed.

CIMMYT joined with the Agriculture Research & Development Center (ARDC) in Bhutan, to host a three-day training workshop. 30 participants from partners including the National Seed Center, the College of Natural Resources, the Bhutan Food and Drug Authority, and other agriculture research and development centers, learned about producing quality hybrid maize seed. The attendees seized the opportunity to propose a formal maize seed system. “This was my first training on hybrid maize seed production, and it was relevant, action-oriented, and applicable to our conditions in Bhutan,” said Kinley Sithup, a researcher at ARDC. Creating a new seed system in

Bhutan shows how CIMMYT provides the environments for co-creating and scaling relevant technologies and disruptive solutions, through strategic partnerships.

During the hybrid maize seed workshop in Bhutan, attendees planned a seed production group, to launch in January 2024. Meanwhile, the country’s ARDC is breeding more hybrid maize with genetic material from CIMMYT. Some of these upcoming hybrids promise to double farmers’ yields. Bhutan and CIMMYT have taken a bold step to develop an entire new seed system for the country. In Pakistan, CIMMYT is helping farmers acquire new seeds as one way of adapting to climate change.

For many years, Pakistan imported wheat. Now CIMMYT is proudly supporting Pakistan’s goal of achieving self-sufficiency in wheat production, strengthening the national economy, and helping to ensure food and nutrition security in the Global South, within planetary boundaries.

From 2021 to 2023, Pakistan released 31 wheat varieties that were well adapted to warmer weather, including 26 new varieties bred from CIMMYT materials. In field trials around the country, over several years, the new varieties yielded about seven tons per hectare, up to 20% higher than popular varieties. The grain quality was ideal for making chapatis, a favorite flat bread of South Asia. The new wheats were resistant to rust diseases, and they could be easily rotated with rice or cotton. Many of the varieties were also biofortified to be high in zinc, helping to fight malnutrition, especially among women and children. The 31 new varieties are just starting to move into the agrifood system, but based on past experience, their use will be transformative. For example, Akbar-2019, a biofortified variety released in 2019, is now sown on nearly 3.8 million hectares. Farmers value its rust resistance, excellent flavor, and its 8 to 10% increase in yields.

The next step will be to produce and distribute enough seed to plant the 31 new varieties on Pakistan’s nine million hectares of wheat land (an area slightly larger than Austria). “Producing and distributing all that seed would be too ambitious for Pakistan’s public sector alone,” explained Javed Ahmad, chief scientist at the Wheat Research Institute, a CIMMYT partner. “Fortunately, our new, fast-track, seed multiplication program collaborates with private companies to multiply seed for Pakistani farmers as quickly as possible.” New seeds and crop varieties help to farm within our planetary limits, especially when combined with appropriate machinery.

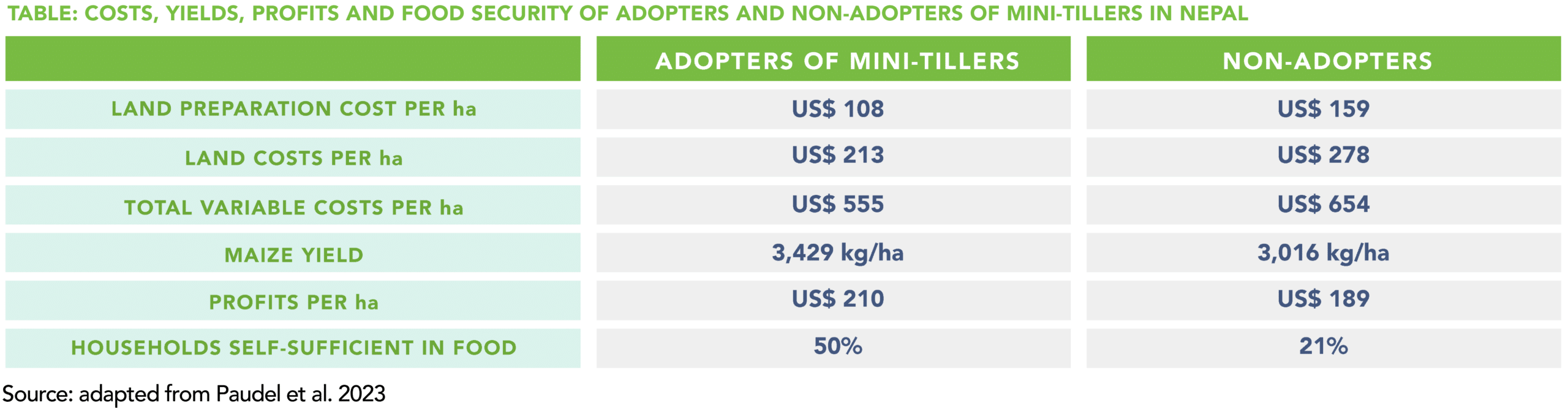

In Nepal’s mid-hills, steep terrain, small fields and a lack of labor make it difficult to plant on time, so maize yields are often low. Machinery can replace lost labor, but tractors need room to turn around, often compelling farmers to remove trees that shelter birds and other wild animals. In Nepal, farmers are starting to use five- to nine-horsepower mini-tillers, which are even smaller than two-wheel tractors.

Two separate studies by CIMMYT show the value of smaller equipment. In Ethiopia, down-sized machines can work on small plots, and under tree canopies, without destroying the habitat that nurtures wildlife, according to a paper published in Biological Conservation, by CIMMYT and partners: the University of Hohenheim, and the University of KwaZulu-Natal. In Nepal, CIMMYT and partners (the Asian Development Bank, and Cornell University) surveyed 1,000 households to determine the benefits of mini-tillers. The mini-tillers helped farmers cut tillage and labor costs. Timely planting increased maize yields, and profits, as reported in the Journal of Economics and Development. This pioneering study was the first to document the correlation between machinery designed for small farms and the UN Sustainable Development Goals: No Poverty (SDG-1) and Zero Hunger (SDG-2).

“Our research can help guide investments by developing countries, supporting rural people who wish to remain on the farm and make a go of it,” explained Gokul P. Paudel, a researcher at CIMMYT and at Leibniz University, who led the study. The adopters and non-adopters were chosen from households of similar economic situations, to ensure a valid comparison. As the following table shows, the adopters of mini-tillers lowered their land preparation costs, their labor costs, and variable production costs, while ramping up their yields and profits. The mini-tiller adopters reported enhanced food security.

CIMMYT’s research shows that machinery adapted to small farms can transform agrifood systems, making them more productive, while conserving biodiversity. Affordable, smaller machinery improves farmers’ livelihoods. This appropriate equipment is easier for female farmers and youth to use, helping to make farming an attractive career, especially for youth and women. CIMMYT will continue to be a global thought leader, transforming agrifood systems by helping governments, NGOs, manufacturers, dealers, and mechanics to foster the right sized machinery. Machinery design may also benefit from other new ideas, for example when people from countries as different as India and Benin put their heads together.

In partnership with CIMMYT, the Green Innovation Centers for the Agriculture and Food Sector (GIC), funded by the German Government, are fostering collaboration between 14 nations in Africa and two in Asia. In 2017, CIMMYT and GIC partnered with Rohitkrishi Industries, an equipment manufacturer, to design machinery for smallholders in India. Based on this success, in 2023 CIMMYT set out to adapt the improved Indian machinery for West Africa.

In 2023, CIMMYT partnered with the Programme Centres d’Innovations Vertes pour le secteur agro-alimentaire (ProCIVA), and a machinery manufacturer, Techno Agro Industrie (TAI) to test Indian six-row seeders in Benin, West Africa. This transformative

collaboration between actors in the Global South has led to practical, scalable innovation. “When developing countries with similar contexts forge alliances to share knowledge with each other, this kind of direct South-South collaboration produces the most sustainable advances in agricultural production, food security, and job creation,” said Rabe Yahaya, agricultural mechanization specialist at CIMMYT.

The collaboration between manufacturers in Benin and India will reshape the agricultural ecosystem of West Africa, as smallholder farming becomes more productive and profitable. CIMMYT is now accelerating South-South collaboration and

win-win partnerships between public- and private-sector actors in other countries, to mitigate climate change, resource degradation, and shocks to global food supply chains. New machinery, like water pumps, are also crucial for irrigation, with its transformative power to improve yields, and adapt to climate change.

Nepal’s food security has been jeopardized by the war in Ukraine. Russia and Ukraine are top exporters of maize, wheat, fertilizers, food oils, and petroleum. The war (and climate change) have imposed hardships on low-income countries like Nepal, which rely on food imports. In Nepal, food prices increased by 10% since 2012, while the price of diesel skyrocketed by 500%. CIMMYT found a solution with small-scale irrigation.

Irrigation can double or triple harvests, improving food security even as conflict disrupts global grain distribution. Most of Nepal’s groundwater is under-used, so CIMMYT advises farmers, governments, and donors on accessing appropriate engineering solutions, while teaching smallholders how to finance irrigation services. There is an emphasis on reaching women and young farmers. Some aquifers run dry when they are over-pumped, so groundwater data must be collected and monitored. CIMMYT has partnered with the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), and the Government of Nepal’s Groundwater Resources Development Board (GWRDB) to develop a novel, digital groundwater monitoring system, reflecting

CIMMYT’s capacity to handle big data and reduce the gaps in knowledge management to support evidence-based decision making. Sustainable irrigation is an ecological solution to improve climate resilience and economic benefits for smallholder farmers.

Farmers and the Government of Nepal are improving their access to key agricultural innovations. As the Nepal experience evolves to boost yields with sustainable irrigation, farmers will strengthen their food security and their resilience to climate change—an example that can be taken to a global scale. In 2024, CIMMYT and partners will improve rental systems for wells and pumps in Nepal, to benefit 20,000 farm households (including 40% women, youth, and marginalized groups). By 2025, CIMMYT will increase GWRDB’s capacity to monitor groundwater in five districts in Nepal, an experience that will be applicable across South Asia. Sustainable irrigation, especially when combined with productive crop varieties and appropriate machinery, showcases CIMMYT’s global leadership in systems transformation, leading to higher

yields and profits for smallholders. In West Africa, CIMMYT is helping smallholders to transition to farming as a career, with another kind of new network: farmers’ hubs.

Poor access to information, technology, seeds, and markets hinders the ability of Nigerian smallholders to produce food. CIMMYT aimed to address this in 2023 with a farmers’ hub in Nigeria that would improve and add resilience to smallholder farmers’ livelihood trajectories.

CIMMYT partnered with the Syngenta Foundation to launch a farmers’ hub in Murya Community, in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. The hub is a one-stop shop for quality seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. The hub helps farmers process and sell their produce, especially food security crops like cowpea, sorghum, groundnuts, and pearl millet, which thrive in warm, dry climates. Farmers who want to get more involved in commercial agriculture can take training courses, rent equipment, process their grain, apply for loans, and receive price information and weather forecasts. The farmers’ hub also partners with universities, governments and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). Collaboration with local stakeholders and international organizations like IITA is crucial for scaling up the model across Africa. CIMMYT partnerships like this one fuel innovation and create sustainable solutions.

If the farmers’ hub in Nigeria links farmers to markets, seeds, and other inputs, the model can be replicated elsewhere. The hub anticipates and addresses changes in value chains, allowing farmers to participate in them to improve their livelihoods. A key challenge will be ensuring fair trade practices for farmers. As the hub both buys and sells products, it will be crucial to establish transparent pricing mechanisms and contractual agreements that protect farmers’ interests and enable them to maintain sustainable livelihoods.

CIMMYT’s accomplishments in 2023 show how agriculture can mitigate climate change,

and adapt to it. CIMMYT is working with leaders in Africa to confirm the crop traits that farmers there will need to adapt to climate change. CIMMYT’s groundbreaking work on wheat anticipates how warmer nights will rob the crop of its yield. Genetic advances will help future plant breeders develop maize that releases less nitrogen into the atmosphere. CIMMYT and partners are breeding maize varieties that improve nutrition, by avoiding anemia and vitamin A deficiency. As a global thought leader, CIMMYT is helping farmers to nourish the world in the midst of a climate crisis, ensuring food and nutrition security, especially for vulnerable regions of the Global South.